It’s about wisdom, not widgets

By Jenni Metcalfe

What is the first word that comes into your head when you think of ‘innovation’?

I asked this question of a group of five scientists the other day.

“Creativity”, said one. “New”, said another. “Silicon Valley”, said a third. “Research”, said the fourth. The fifth scientist looked thoughtful and proceeded to give a short speech.

I have been pondering the word ‘innovation’ ever since the Australian Government decided to make it central to their science policy after releasing the National Innovation & Science Agenda Report late last year.

It’s a word that seems to get dug up every few years as something ‘new’ that Australians should aspire to.

I’m unsure if innovation is a process or a product but I’m concerned that many people see it as mostly applicable to high-tech manufacturing and IT rather than research for the public good.

Now more than ever we need creative ideas to address the big public issues of climate, health and social wellbeing. And science communicators need to be part of the mix, facilitating innovative means of achieving solutions.

But what is ‘innovative’ science communication when tackling intractable problems?

As science communicators, if we are to be truly creative in helping positive change we need to bring WISDOM to the table by considering:

- Who needs to be involved in innovative research – and it’s not just scientists

- Individual perceptions, concerns and needs of all players, right from the start

- Social face-to-face meetings – not relying on email, phone, and video links

- Developing a shared vision between all players

- Opening up dialogue between players with different knowledge and values

- Managing interactions to make sure all voices are listened to.

Bringing WISDOM to the table: Longreach graziers tell Bureau of Meteorology and CSIRO climate researchers what they want from seasonal forecasts and pasture models.

Image: Econnect Communication |

|

Boiling down the science – the master stock

By Mary O’Callaghan

I really appreciate when people get to the point quickly, especially in writing. And I know how hard it is to write short because it’s what I spend a lot of my time doing—summarising research papers, shrinking executive summaries, culling bloated first-draft feature stories (my own too), pulling apart the sandwich looking for the meat.

Luckily I enjoy it. To me it’s like cooking up a big pot of stock. You start by chucking in all the ingredients but it’s a bit watery; bland really. You gradually reduce it over many hours until you are left with a rich potion in which every ingredient is pulling its weight and contributing to the flavour and substance of the whole.

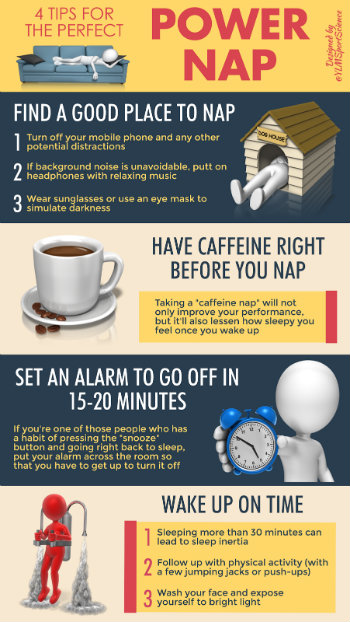

Yann Le Meur has an interesting (dare I say, innovative) approach to summarising research papers in the field of sport science. He knows that most of us don’t have time to read lengthy articles so he does us a favour and boils them down to their essence.

He distils the important messages and presents them with amusing graphics in a form that’s easy to read and, mostly, easy to understand.

Even if you’re not a sport scientist, you can generally get the message from his infographics (I had to look up ‘euhydrated’ – it means the body is in a normal state of hydration – not dehydrated (hypo) and not over-hydrated (hyper)).

Read Yann Le Meur’s blog: Sport Science Infographics and follow him on Twitter: @YLMSprtScience

Still too much to take in? No problem—the team of Canadians behind Useful Science promise to tell you something useful in just 5 seconds. Malcom Gladwell calls it ‘genius’.

Here are a few Useful Science examples:

Each micro-summary is linked to the original journal article.

Now, time for a coffee and some creative thinking, followed by a nap. |

|

Wicked problems need cross-disciplinary innovation

By Melina Gillespie

Nanotechnology crosses the fields of physics, biology and chemistry.

Disease management requires expertise in public health, behavioural science, communication, biostatistics and epidemiology.

Original and great ideas often come from looking at, and understanding, the big picture. So crossing disciplinary boundaries is as important as advances in specific disciplines.

Innovation in science also comes from creating strong partnerships with those who apply the research.

Industry partners in the University of Adelaide’s collaborative research in photonics (the science and technology that generates and controls light), for example, are from aerospace R&D, irrigation management, fertility clinics and wineries.

To tackle wicked problems—especially those problems that have become serious global megatrends, such as water and food scarcity; biodiversity loss; the changing climate; and our ageing population—we need innovative science that prompts change.

One example of a wicked approach is The Ocean Cleanup, a crowd-funded initiative that aims to clean up the Great Pacific ‘garbage patch’—the accumulation of discarded plastic which is now so big that it can be seen from space—while also preventing further pollution.

Communication within collaborative research projects is challenging. At Econnect, we have researched this area, and teased out important points for collaborating across the HASS and STEM sectors [PDF], and between research and industry.

Our workshop and booklet on planning science communication highlight things to consider when communicating in a collaborative environment:

- Take the time to develop trust and relationships.

- Encourage, support and kindle the passions of the people involved.

- Be aware of and work at overcoming the cultural and language barriers between organisations and disciplines.

- Create shared stories.

- Make sure all partners come to the table at the same time with the same status so that relationships are equitable.

|

|

Game of science

By Jay Nagle-Runciman

Blogs, vlogs, podcasts, pictographs, infographics, social media, curation sites such as Pinterest and Storify—we are hybridising media platforms all the time.

We are making them new; innovating.

And now we have made new the concept of a game.

When the mainstream media started using gamification—using game design, concepts and mechanics to engage people—I was cynical.

But it seems to me, it may just have found its perfect home here in science communication.

Using game design for communicating scientific concepts not only engages people, with so many online gamers it can also yield mass information for researchers.

Here are three great examples of gamified science concepts:

- Eyewire has turned mapping the human brain into a game. Players are challenged to a 3D puzzle, with rewards for accuracy, speed and creativity. It’s an online game, and every player contributes to a digital model of the brain, in an effort to understand the connections among our neurons, or what lab leader Sebastian Seung refers to as the ‘Connecttome’.

- Foldit players try to solve the puzzle of how proteins fold. In cells, the form of a protein determines its function – from growth and repair to cell reproduction or even destruction. Players must follow the same rules that exist in real protein formation. Because proteins are involved in so many cellular processes, figuring out how they form and what their shape is can help in many research areas. Within 3 weeks of the game’s release, players had helped to figure out the shape of an enzyme that had stumped AIDS researchers for decades.

- Eterna is the next step on from Foldit. It focuses on RNA (ribonucleic acid) molecules. It starts out with basic games and rules and eventually you can build your own molecules and submit them to the scientists who then make them.

Foldit: Unfolded streptococcal protein puzzle

In Gamification leads to era of armchair scientists, Varun Saxena goes into more depth, and even gets you thinking about the concepts of collective human intelligence being greater than any supercomputer.

Gamification is part of the larger trend towards convergence in the media. There is also convergent science, where, increasingly, whole sub-disciplines of science are starting to converge; for example, health and computer engineering.

Everything is converging, it would seem. |

|

|